Henry Newbolt’s Vitai Lampada was typical of the war poem of the 1890’s, aping the heroic images of Tennyson: “The Gatling’s jammed and the Colonel dead/ And the regiment blind with dust and smoke;/ The river of death has brimmed his banks,/ And England’s far, and Honour a name;/ But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks:/ ‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’” The intention of this kind of poetry was to stir the heart of the reader with pride and fill the head with awe at the magnificent bravery that separated the Englishman from his rivals on the battlefield. It allowed people from any social class to feel that they were part of something precious. Certainly, Vitai Lampada was hugely popular with soldiers and public alike upon its publication in 1898, but by this time a new kind of war poem was coming to prominence, one whose roots lay in the growth of radical thought and humanitarian opposition to war.

“The Voice of the Hooligan”

The poet most synonymous with, and if some were to be believed responsible for, the war was Rudyard Kipling. To his many detractors he was the Bard of Bloodshed, an apologist for aggressive Imperialism. They could point to If, inspired by Jameson and Rhodes, or the Barrack Room Ballads’ hooliganism in the name of Queen and country. He became a popular target for the pro-Boer press. One issue of Justice mocked his fund-raising efforts: “O God of Battles, by whose fire/ Thy Kipling warms his brain;/ How blest are they who only pay/ While other men are slain!”

Kipling had always been far from uncritical of the Empire, but held a firm belief in what it could be as a moral ideal. Deemed medically unfit to enlist, his prose and verse betray a boyish fascination with adventure. While most writers concentrated on the officer as hero, he popularised the everyman army figure of Tommy Atkins – a loveable rogue doing his duty for Queen and Country. Kipling’s talent lay in understanding public sentiments and expressing them in verse designed for the music hall. After the colossal success of the Absent-Minded Beggar Kipling travelled to South Africa to help distribute the supplies bought with the funds raised by the song. His concern for the ordinary soldier had made him a hero out there, and he became guest-editor of the armed forces’ first ever newspaper, The Blomfontein Friend. Kipling realised the effect his patriotic fervour had on his reputation. Of the Absent-Minded Beggar, he said, “I would shoot the man who wrote it, if it would not be suicide”. Having witnessed the strains brought upon the troops through poor leadership and training at first hand in South Africa, Kipling’s later works show disillusion with the old aggressive Imperialism that had brought about the conflict. The Dykes from 1902 begins: “We have no heart for the fishing- we have no hand for the oar-/ All that our fathers taught us of old pleases us now no more.”

Kipling had always been far from uncritical of the Empire, but held a firm belief in what it could be as a moral ideal. Deemed medically unfit to enlist, his prose and verse betray a boyish fascination with adventure. While most writers concentrated on the officer as hero, he popularised the everyman army figure of Tommy Atkins – a loveable rogue doing his duty for Queen and Country. Kipling’s talent lay in understanding public sentiments and expressing them in verse designed for the music hall. After the colossal success of the Absent-Minded Beggar Kipling travelled to South Africa to help distribute the supplies bought with the funds raised by the song. His concern for the ordinary soldier had made him a hero out there, and he became guest-editor of the armed forces’ first ever newspaper, The Blomfontein Friend. Kipling realised the effect his patriotic fervour had on his reputation. Of the Absent-Minded Beggar, he said, “I would shoot the man who wrote it, if it would not be suicide”. Having witnessed the strains brought upon the troops through poor leadership and training at first hand in South Africa, Kipling’s later works show disillusion with the old aggressive Imperialism that had brought about the conflict. The Dykes from 1902 begins: “We have no heart for the fishing- we have no hand for the oar-/ All that our fathers taught us of old pleases us now no more.”

The popular belief that the English race had been chosen to carry out the work of a Higher Power was reflected in Alfred Austin’s Alfred’s Song. Along with Swinburne and Henley, Austin saw the forces of the Empire as modern knights. That Austin had become the current Poet Laureate shows the hysteria that had engulfed the country, and hundreds of would-be poets tried their hand at producing verse to celebrate England’s supremacy. As Salisbury wrote to Queen Victoria, “It is to the taste of the galleries in the lower class of theatres, and they sing it with vehemence.” Henley’s Song of the Sword established the blade as a Divine instrument to separate the weak from the strong. Swinburne regularly donated work to the papers to rouse the spirit, from Transvaal, with the infamous closing line, “Strike, England, and strike home,” to The Turning of the Tide. There was an early notice of the new mood in poetry after Transvaal’s publication in the Times, after W.H. Colby constructed this reply: “Where are the dogs agape with jaws afoam?/ Where are the wolves? Look, England, look at home.”

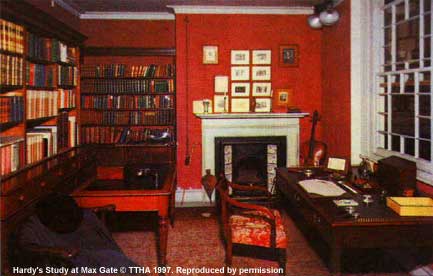

Hardy and the War

Thomas Hardy was disappointed with Transvaal, noting in a letter to a friend it was probably rattled off in a hurry. He was determined that his work would not have any of the fatal defects of Jingoism. Hardy did not disagree completely with Britain’s policies, but he could not understand the triumphalism in some quarters at the prospect of another war. He was less concerned with the greater issues than the experiences of those fighting and dying thousands of miles from home. The husband of his close friend and confidant Florence Henniker was a major in the Coldstream Guards, and his communications with her betray Hardy’s disenchantment: “I constantly deplore the fact that ‘civilised’ nations have not learnt some more excellent and apostolic way of settling disputes than the old & barbarous one.”

Thomas Hardy was disappointed with Transvaal, noting in a letter to a friend it was probably rattled off in a hurry. He was determined that his work would not have any of the fatal defects of Jingoism. Hardy did not disagree completely with Britain’s policies, but he could not understand the triumphalism in some quarters at the prospect of another war. He was less concerned with the greater issues than the experiences of those fighting and dying thousands of miles from home. The husband of his close friend and confidant Florence Henniker was a major in the Coldstream Guards, and his communications with her betray Hardy’s disenchantment: “I constantly deplore the fact that ‘civilised’ nations have not learnt some more excellent and apostolic way of settling disputes than the old & barbarous one.”

Hardy had cycled to Southampton to see Buller and the troops off on their way. The emotions on the faces of the people on the ships and at the quayside — excitement mixed with foreboding – were captured in his poem The Departure (later titled Embarcation), published in the Daily Chronicle on 25 October 1899. His most memorable work, Drummer Hodge, concerns an unspectacular soldier, the victim of a conflict beyond his understanding, whose remains are valued as something precious by the landscape that has become his new home: “His homely Northern breast and brain/ Grow to some Southern tree.” The unlamented Hodge is now part of a larger, cosmic picture, against which the war pales into insignificance. A Christmas Ghost-Story dates from the same period, and was published in the Westminster Gazette on 23 December. It is deliberately ambiguous; the ghost could be either a Boer or a Briton, and the underlying theme lead to Hardy being accused of pacifism by an apoplectic Daily Chronicle on, of all days, Christmas Day. The Souls of the Slain shows a commitment to ordinary, unheroic values. The ghosts of soldiers killed in battle return home to bask in the glory of their deeds, but are met by “a senior soul-flame” who shows them that they are remembered for dearer things by their loved ones, not their sacrifice for Queen and country.

Anti-War Poets at Home

William Watson had railed against the abandonment of Gladstonian Imperialism in the years before the war. Ignoring the inevitable accusations of anti-patriotism, verse such as The Enemy portrayed the Boer possessing simple qualities Britain had long since lost to industrialisation. His sales dropped by sixty per cent between 1899 and 1902.

The death of his brother Herbert at the front gave A.E. Housman’s work a more poignant edge. Astronomy shares similarities with Drummer Hodge, contrasting the vastness of the cosmos with the aspirations of one glory-hungry soldier.

One of the most affecting poems of the war was Slain by T.W.H. Crosland, which appeared in his magazine Outlook in November 1899. Crosland was one of the fiercest critics of Kipling’s naïve faith in Rhodes, and parodied Kipling’s boorish style in the Absent-Minded Mule, going so far as to copy the layout and typography. However, Slain was a poem that could stand on its own merits, possessing much in common with the better known war poems of 1914.

Poets at the Front

For the first time Britain had sent a fully literate army to the battlefield. Regular Tommies hailing mostly from the lower classes were able to put their experiences down on paper. There were also the Volunteers that made up half the total of men committed to South Africa who came from all walks of life. Much of the poetry was based upon the traditional army songs that went back decades, or Kipling’s populist verse. Some of the more critical work found a home in the radical press. These works fascinated the public because they came from first-hand experience, whereas poets at home could only base their work on reports from others.

An in-depth look at Drummer Hodge

Links:

Recommended reading:

Drummer Hodge: the Poetry of the Anglo-Boer war (1899-1902), Malvern van Wyk Smith, 1978

Chapter 13: The South African War: the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902, Ed. Peter Warwick, 1980

Hardy’s Poetry 1860-1928, Dennis Taylor, 1989